Jade Vineyard is one of China’s finest young wineries and its owner Emma Ding is on a mission to make its wines iconic. But how do you achieve global success in a world of politics? Ben debates how a winery as good as Jade Vineyard could establish itself in new markets, as long as it has the patience and drive to do so.

Just before we all had our lives turned upside down by Covid-19 and lockdowns, I had the pleasure of tasting a flight of the finest wines I’ve tried. I’d been invited to the Decanter Fine Wine Encounter event in The Landmark, London, where a host of the best producers were offering their wares, to taste Emma Ding’s Jade Vineyard wines.

The invite had come from Richard Morley, ex-Decanter now First Pour consultancy, who had mentioned Jade Vineyard at the Novel Wines annual tasting in 2019. He had described to me a pioneering winery that was doing something truly special. He was confident I’d love the wines.

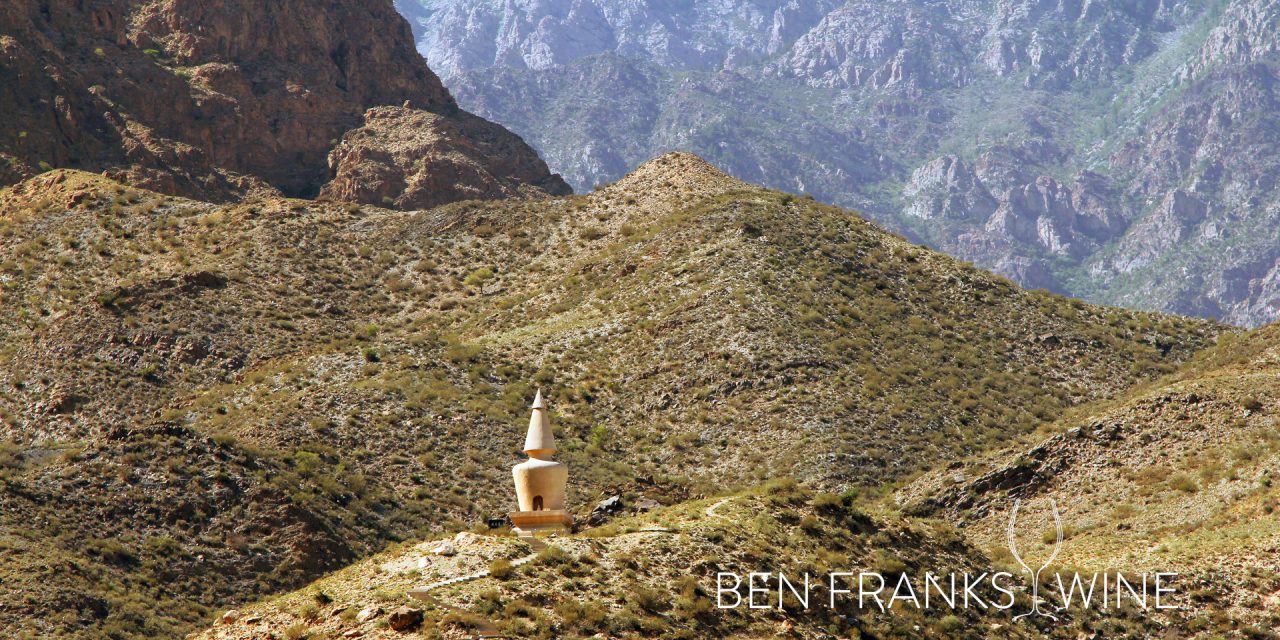

He was right. Jade Vineyard is planted in Ningxia near the Helan Mountain range on rocky soils in an extreme continental climate. Hot summer days and freezing winter nights characterise the region, sat some 1180m above sea level. Emma Ding, a banker turned wine merchant, knew this was the place she wanted to plant a vineyard and she wasn’t going to do it by half measures, employing one of China’s best winemakers Shuzhen Zhou. The wines launched to international acclaim and I could not wait to try them.

I was also excited to be at Decanter Fine Wine Encounter. It was an event I’d not been to before but some winemakers I knew well were exhibiting, so I visited them first and was lured in to tasting some true classics from the New World that I rarely get to taste. It was a little like being a kid in a sweet shop.

Then I met Emma and tried the wines from Jade Vineyard.

“How do I get these wines?” I asked immediately after spitting the final wine. It was like I’d wandered ride to ride in a theme park and was having a pretty good time, only to suddenly step off the last ride truly exhilarated and wanting to repeat the same experience over and over. The wines were that good.

But they weren’t in the UK. Novel Wines is successful but setting up a brand-new import route from China was a no-go. And then again, here were hundreds of wine experts around me tasting the same wines. Surely someone here would bring these wines in and I could list it through them?

For some reason no-one did.

For me, start-up firefighting and the pandemic got in the way of pushing for a solution. Occasionally I’d hear about them on the grapevine and ring around to see if they were in the UK yet, ready to buy a case or two and see how they’d go. Each time I found out they weren’t available. It wasn’t until I was invited to a Three Wine Men event with Oz Clarke to try Jade Vineyard wines in 2022 that I thought about it all over again. How do I get these wines Someone must bring them in?

Emma had told Club Oenologique in 2021 that she was driven to go ahead with making her wine in China because “there was a huge gap in the market for fine wine in China”. It’s easy to see – especially having effectively banned Australian wine imports and taxing other countries’ wines to kingdom come – where she’s coming from. A home-grown, premium and fine tasting wine for an increasingly wine conscious market is ripe for the picking. China’s growing wine loving community would almost certainly drive commercial success and realise her ambition. But Emma’s other dream to become an “iconic winery” on the international stage might prove more difficult.

For all the love I’d gained for these wines, despite having only tasted them twice, I started to realise that I was risk averse. I wanted the wines but only a case or two, to dip my feet and see how things might go. I started to struggle to reconcile with how I’d make them work here in the UK. Yes, they taste great. Yes, Emma’s drive and her story is as impressive as some of Europe’s finest winemakers and business owners. Yes, they even look good – no mean feat for an emerging market.

But how many people are going to buy Chinese wine?

And how many people will do it at the pricepoint Emma desires?

The Hyacinth red is £50 a bottle in Hong Kong and her flagship top red Messenger is £190. In the UK the prices would be higher still – driven up by logistics and taxes.

These wines may taste sublime and an argument for the quality justifying the price is an easy one to make, if you’ve tried them. The challenge to sell it lies in its origin. China is a rich culture with a long history. There is magic and intrigue that gives it ticks in the plus column in the same way Japan or Peru might conjure. But modern China is so anti-west in its politics and in the portrayal of our media that it principally struggles to be attractive because a majority of western consumers don’t trust China. Any salesperson knows that trust is the only way you can sell a premium item. While we might use Chinese manufactured goods every day, in the world of wine so much attention is paid to provenance and origin that China is highlighted far more clearly in wine than it is in any other product. OK, you could get a customer to taste the wine and sell them on quality, but we’re forgetting the practicality of importing these wines. Long haul import means large minimum order requirements and pricey cashflow commitments. It means the importer has the pressure to flog lots of stock, and when you need all your customers to try before they buy then you’re going to be visualising your resources go up in flames to get there.

So how do you do a winery like Jade Vineyard justice? It seems such a shame to leave wines this good out of the UK market, especially because it proves China can make wine just as well as anywhere else.

The problem of politics stunting wine’s appeal is not a new one. Hungary’s drift from democracy to semi-autocracy is a worrying transition for merchants like mine that have a significant list of Hungarian wines, and it is a worrying drift for the wineries who are investing in a similar drive for iconography in places like Tokaj, who are trying to reinvent Aszu and return to the golden age where it was regarded as one of the finest wines around. The problem also follows around the wines of Israel and the wines of Palestine. Politics burns bridges in trade while differing ideologies build hurdles to new markets.

So how do you fix the issue? Supply must meet demand and demand creation for wines needs to come from a place of trust.

Jade Vineyard then has one clear market it can start with: familiarity. Chinese expats abroad or western businesspeople who work with or in China. This niche market will be an easier one for wineries like Jade to open up to because they will know China, some of its culture and its politics. They will be warmer to it because they do business with it. Many of them will even have visited there. Many of them will have expendable income. As with all great wines, this will open the door to word of mouth amongst high income wine lovers. It will lead to the inevitable pop up in wine tasting menus at London’s elite wine clubs or private members’ dining. It will start to seed in the market.

As these seeds start to germinate, maybe the hurdles will start to lower. As long as quality and brand are strong – and more and more people taste the wines – the hurdles will lower still. The creation of this market is slow, but not impossible. The key challenge is going to be that no winery becomes iconic overnight and only those with the stamina and drive to see it through will win.

Of all the wineries China might produce in the years to come, Emma Ding’s Jade Vineyard – I am sure – will have the drive.