Happy New Year! Ellie Scott reflects on a recent trip to Mendoza in Argentina and the producers’ unique opportunity to mould the land and their wines they desire. With so much diversity on offer, how are the wineries of today shaping their future?

Ask someone to close their eyes and picture a wine region, and there’s a good chance the imagined picture has green hillsides and contoured vineyards. Mendoza is unlike other wine regions. Here most vineyard sites are flat, and there is just so much space. Unobscured views to the snow-capped peaks of the Andes only serve to highlight the sheer scale of the region. If you were to tear your eyes away for a moment from the beauty of the ever-present mountains, you would still feel their influence. The dryness of the air, the powerful sunlight, the dustiness of the roads. Mendoza is really a high-altitude desert, with vineyards planted in large oases around rivers and benefitting from snowmelt.

The province of Mendoza is home to over 800 wineries across 150,000 hectares, only a tiny fraction of the land. Many vineyards are covered with netting to protect from potentially catastrophic hail, the most high-tech made from plastic and Kevlar (the fabric used in bulletproof vests) and costing up to USD 10,000 per hectare. Many vines are ungrafted, and if rootstocks are used it tends to be for protection against more problematic nematodes than phylloxera.

Netted vines at Finca Decero

Although vines were first brought to Argentina by the Spanish in the 16th century, it was foreign interest in wines from Argentina in the 1990s that kickstarted a boom in Mendoza. Taking advantage and concentrating on export markets has not only helped many wineries weather an increasingly rocky domestic economy, but also to strive for quality. Part of that endeavour has been an expansion to cooler vineyard sites, which means looking either to higher latitudes or higher altitudes. As a result, many of today’s wineries were the first to cultivate the land on which they now stand.

Organic viticulture in Mendoza

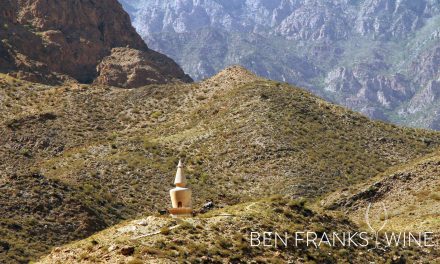

When Jean Bousquet arrived in Tupungato in the Uco Valley in 1990, there were no vines to be seen, in fact almost nothing to be seen at all but scrubland and mountains. Jean, a third-generation winemaker from the south of France, fell in love with what he saw as the ideal site for organic winemaking. Jean’s daughter Anne, who took over the business with her husband Labid Al Ameri in 2011, says it was an easy decision to farm organically – if you can’t make organic viticulture work in almost desert conditions, where can you?

On the flip side, it is perhaps understandable that with such infrequent need to use chemicals, many wineries don’t see it as necessary to convert to farming organically. Others, like Riccitelli, do work organically but regard certification as unnecessary. This may change as the market and consumer demand for organic wine continues to develop. In the meantime, Domaine Bousquet remains the only fully organic winery in Argentina, and they are pushing their focus on sustainability even further, becoming certified as biodynamic with Demeter in 2021 as well as being the first winery outside of the US to be certified ROC (Regenerative Organic Certified).

This is surely the epitome of what it should mean to be a ‘New World’ wine region – the opportunity to plant on virgin soils and mould the land and wines as desired, with a modern understanding of both viticulture and winemaking. In Mendoza the relatively recent plantings mean an ability to take advantage of greater viticultural and geological knowledge and new technologies.

Terroir and technology

Modern technology is being used to its full advantage to map the hugely diverse soils in the region. Alluvial fans are complex geological formations, triangular in shape and formed as water or rocks move down a mountain bringing silt and rocks of different sizes, spreading out as they reach lower slopes. Forty alluvial fans have been identified in Mendoza, and overlapping fans can further complicate the geology.

Zuccardi’s Piedra Infinita winery in the Uco Valley, Mendoza.

Zuccardi’s famous Piedra Infinita winery lies in Altamira Sur, part of the Tunuyán fan in the Uco Valley, boasting calcareous soils and large rocks. It took Zuccardi eleven years to map the soils in the Piedra Infinita vineyard using soil pits and electromagnetic mapping. They are far from the only winery undertaking soil investigations. Finca Decero and Bemberg Estate are amongst others building up beautifully complex soil maps resembling modernist paintings. The Catena Institute, founded by Dr Laura Catena of Catena Zapata in 1995, performs in-depth studies of not just soils but everything related to vineyards in the region and beyond, with the aim of elevating Argentinian wine.

The wines and soil map at Zuccardi.

At Zuccardi, before such studies were undertaken, it became clear at harvest that picking had to be done almost vine by vine, such was the disparity in ripening. Even where the composition of soils does not vary widely from row to row, the depth of each layer waxes and wanes in meandering contours. While at Piedra Infinita, grapes have to be picked in ‘polygons’ following the lines of the soil maps, vineyard mapping allows more recent vineyards to be planted in a more organised way, taking advantage of the best areas for particular varieties.

The nuances: subregions and parcel wines

Because of the diversity within single vineyards, small parcel wines are becoming more common as winemakers endeavour to focus on terroir. Given the ubiquity of the country’s best success, Malbec, terroirs seem both an easy and important method of distinction. At Bemberg Estate they call their wines ‘a terroir tour of Argentina’ focusing on single terroir fine wines, such as Finca El Tomillo in Gualtallary, planted on an alluvial fan from Las Tunas River.

Winemaker Tomás Hughes showing soil pit at Finca Decero

Bemberg Estate

Terrazas de los Andes make a ‘Parcel’ range of Malbecs showing distinctive differences in plots, from the herbal notes of Malbec planted in the sandy soils of Gualtallary to the concentrated structure of Malbec from Los Chacayes further south in the Uco Valley.

Catena Zapata’s premium White Bones and White Stones Chardonnays are selected from specific rows within their Adrianna Vineyard in Gualtallary, and named to reflect the underlying soils of the vines planted only metres apart. Mil Suelos, whose name means a thousand soils, likewise want to celebrate the diversity in Argentina’s soils, producing vinifications from small sites aiming to show that small distances can mean big differences.

The Uco Valley has been on even the casual Malbec drinker’s radar for a number of years, and at around 45 miles long and 15 miles wide, it is unsurprising that subdivisions are becoming increasingly well-known, with districts including Paraje Altamira and Los Chacayes already named as GIs, and others like Gualtallary likely to follow.

The future of Mendoza wines

With so much diversity offered by the wines of Mendoza from grape varieties, producers, and styles, as winemakers drill down further into the diversity of terroirs in the region and celebrate the nuances they bring to the wines, this can only be a good thing for consumers.

—-

Photos and words by Ellie Scott.

New World, virgin territory, weather challenges but still the viticulture succeeds with modern solutions, absolutely fascinating, thank you!