Inspired by a visit to Westwell Wine Estates, Kris Pathirana looks at how we can better champion English sparkling wine as a core part of celebrating England and our Englishness.

It is no secret that wine tastes best when imbibed about a hundred feet from where its grapes were grown. Admittedly, it doesn’t hurt if you happen to be standing in the rolling hills of Tuscany, or close enough to the California coastline to smell the Pacific air, but the tangible connection between grape and glass just makes tasting wine at a vineyard an elevated experience. Yet one wonders whether it would be quite as delicious if you were standing in a field in Kent off the A20?

There is something about England that makes us a tad resistant to hyperbole for anything on our own doorstep. Maybe it is our penchant for sarcasm and suspicion of braggadocio that causes us to snap a collective eyebrow when, for example, people unironically describe Torquay as ‘The English Riviera.’ I feel a similar jolt when people wax a little too lyrical about English sparkling wine – presumably, the same people who are still trying to make ‘fetch’ happen. “It’s as good as champagne,” they insist. Not only is this dubious, but it is predicated on the notion that all champagne is created equal. In fact, it could be argued that the disparity between good and bad champagne is larger than the gap between good and bad English sparkling. Yet even if the peak of Anglican fizz is some way from hitting champagne’s heady heights, as anyone who has tasted Emma Rice’s wines from her stint making Raimes can tell you, English sparkling is on the ascent. Rathfinny in Sussex, the late Steven Spurrier’s Bride Valley in Dorset, and my personal favourite, Westwell, are all making excellent English sparkling well worth their price tags.

I first discovered Westwell through their flagship ‘Pelegrim’, a non-vintage sparkling made in the Traditional method; and this summer I had the good fortune to visit their vineyard in a field in Kent off the A20, to taste some of the best wines being made by anyone, anywhere in Britain. Westwell’s vineyards are eighteen lusciously green hectares on the chalky slopes of the North Downs, about an hour’s train journey from London. Located just beneath the Pilgrims Way, it was once a route used by Pilgrims travelling to Canterbury.

Westwell Vineyard

After a warm and informative tour of the vineyard from our guide Claire Butcher, the Cellar Door & Production Manager Jeanette Lithgo treated us to a dosage tasting. ‘Dosage’ refers to the amount of sugar added to a Traditional method sparkling wine after disgorgement (removing yeast from the bottle) before the insertion of the cork. The amount of sugar dictates not only how dry the wine will be, but acts like ‘wine seasoning’, enhancing and balancing flavour profiles.

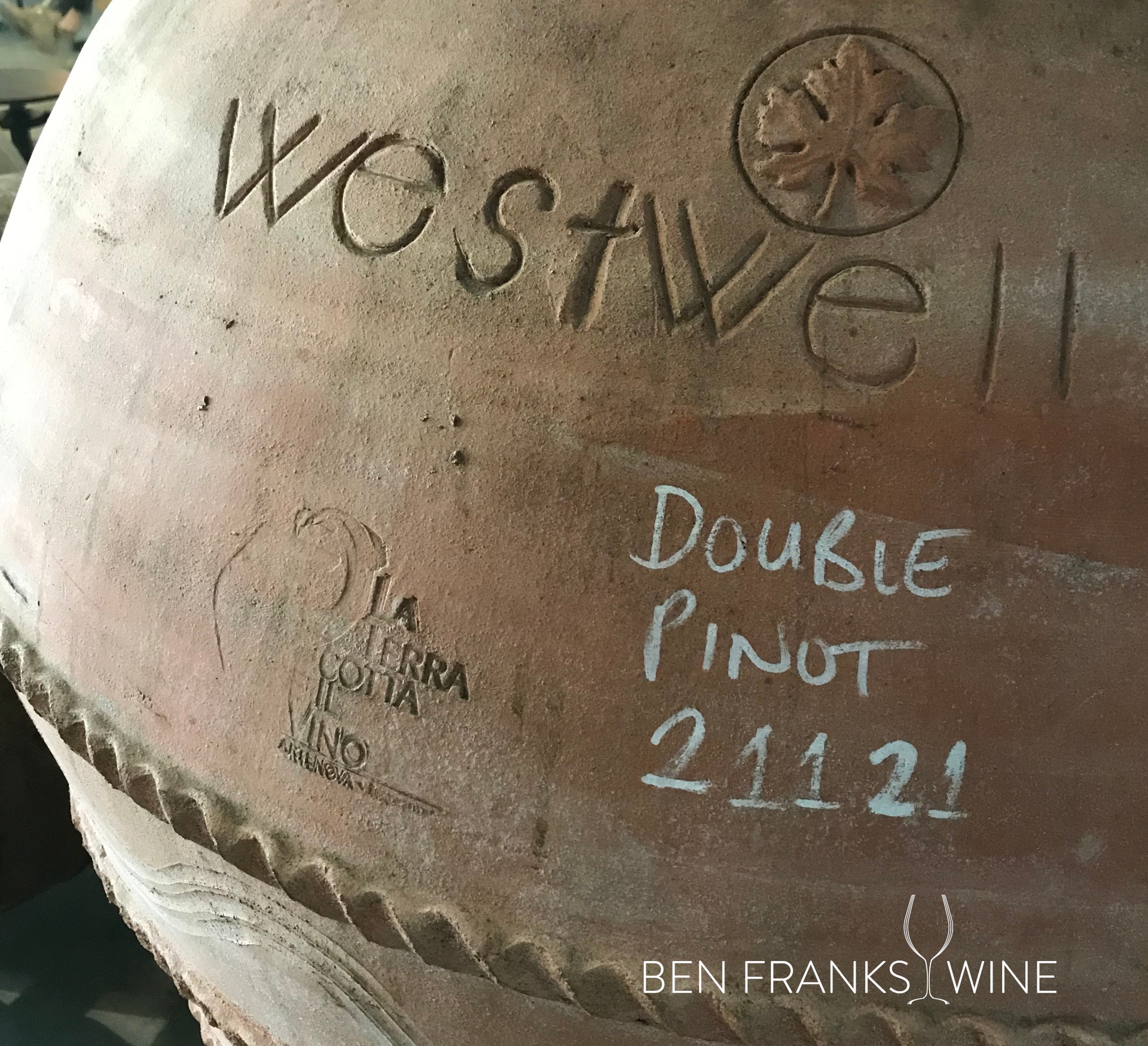

Lunch was served in the sunshine on a beautifully present table outside the cellar, a fabulous homemade spread of sausage rolls, spinach and feta parcels, and heirloom tomato salad with anchovies. Ruth Spivey, the Cellar Door & Programming Manager, then guided us through the wines. There is a pride of ownership and an almost commune feel exhibited by the women who work here, as if there was an entire world that existed solely within the realm of the vineyard; a found family that had purged the need for anything but what they could grow, age, and ferment themselves… alternatively, they might just enjoy working here. I was particularly excited to try Westwell’s recently released ‘Double Pinot’, a red blend of Pinot Noir and Pinot Meunier. Despite my underwhelming experience of English reds, I was taken in by the snappy name. It was brought out chilled and decanted, and while a little delicate for my own Fee-fi-fo palate, the Pinot² paired perfectly with our light lunch. Now, I am not generally a Pet Nat guy, but when the ‘Naturally Petulant Pink’ arrived, this absolute jewel of Kent – the same Kent that shall henceforth be known as ‘The People’s Tuscany’ – changed everything. With the most beautiful rose quartz colour, fraises and tarte citron on the nose, and ripe raspberries and fresh white peach on the palate, it was an absolute showstopper.

Double Pinot

As the sun sets, nobody can quite believe that we are in England. Not because it feels continental, but because it feels so decidedly English. And yet. This is not simply good ‘for England’ – this is good for anywhere; a perfect marriage of expertise, graft, and love – all qualities that seem in short supply of late. So, why isn’t something so local and community-based a larger part of our culture? Why aren’t we championing this as an example of English excellence? Why isn’t this used to incentivise tourism? Perhaps part of the problem is we do not yet have the necessary nomenclature for English sparkling. There isn’t an umbrella word like Champagne, Crémant or Cava to describe it. We have to call it, “English sparkling,” which is not exactly catchy, and sounds vaguely apologetic. “It’s sparkling! But uh… English.” This lack of identity feels like a self-fulfilling prophecy, sentencing English fizz to be described only in the context of its celebrated counterparts.

The other challenge with ascertaining an identity for English sparkling is that English identity itself is a peculiarly nebulous idea. Having grown up in Wales amidst Eisteddfods, rugby, and the firm conviction that Dylan Thomas was the greatest poet of all time, patriotism was very much about what was Welsh and being Welsh. In England, patriotism feels very much about defining who is not English. Not what is English. Within this vacuum, bad-faith Slender Men fill the void with shameless mendacity about British waters now containing British fish, vague yet somehow hill-to-die-on beliefs about sovereignty, and for some reason, an impassioned, Dickensian advocacy for poor children missing meals. Yet beyond the vacuous noise lies precious little as to what is exceptional about England; things we can hold, taste, and see. Again, this is somewhat understandable given that even the ‘British’ museum is mostly an array of the ‘indefinitely borrowed’ from nations indefinitely damaged by Empire. England, by definition, is a collection of other people’s things.

When I was a child, the then Prime Minister John Major said that in fifty years Britain would, “Still be the country of long shadows on county [cricket] grounds, warm beer, [and] invincible green suburbs.” I remember hearing that and feeling resentful at how unambitious and parochial he made us sound… but as it turns out he was making an entirely different point, one not only missed by my childhood self, but many current politicians. I now find myself pining for the days when the worst generalisations of Englishness were that we were quaint; when it seemed that we were only a small island and not a small people. But like an American in London hoping to find a befuddled Hugh Grant, and finding only human missed child support payment, Lawrence Fox, we are in a less Brave New World.

So, it is with considerable relief that despite coming of age during the most divisive political period in recent memory, English sparkling has avoided being hijacked by the nativist narrative and shoehorned into a phony culture war. However, there is a bipartisan opportunity here, to reaffirm the difference between national pride and nationalism, between championing English accomplishment and yelling imagined superiorities into an empty bag of Frazzles. Going to an English vineyard is a wonderful day out and should be showcased by every tourist board on the south coast. Not only is this a fantastic way to support farming communities and buy your wine locally and sustainably, but it is also an opportunity to help rebrand post-Brexit Englishness as something more than the anachronistic wet-dreams of grifting, double-barrelled, nepo-babies.

There are significant benefits for tourism, trade, and the economy, if we make English wine (and visits to our local vineyard) part of the modern fabric of our culture – and it need not stop at wine. There are hundreds of incredible breweries and distilleries all over the country that could thrive with mainstream support. If we did this, thus celebrating real things, perhaps we would not cling quite so tightly to illusions of greatness we played no part in. We might also find that it is possible to champion England and Englishness without it descending into bigotry, or a game of two twats, one cup, by men in red corduroy trousers.

So, get yourself to your local vineyard. Make a day of it. And who knows? Perhaps if we shout loud enough, we will discover it to be something that even in these times, we can all agree on… and perhaps if we shout louder, it will entice even the most conventional of European oenophiles to visit the likes of a field in Kent off the A20 and say wildly hyperbolic things like, “You know… English sparkling really is as good as champagne.”